Helen Eliza Garrison: A Memorial.

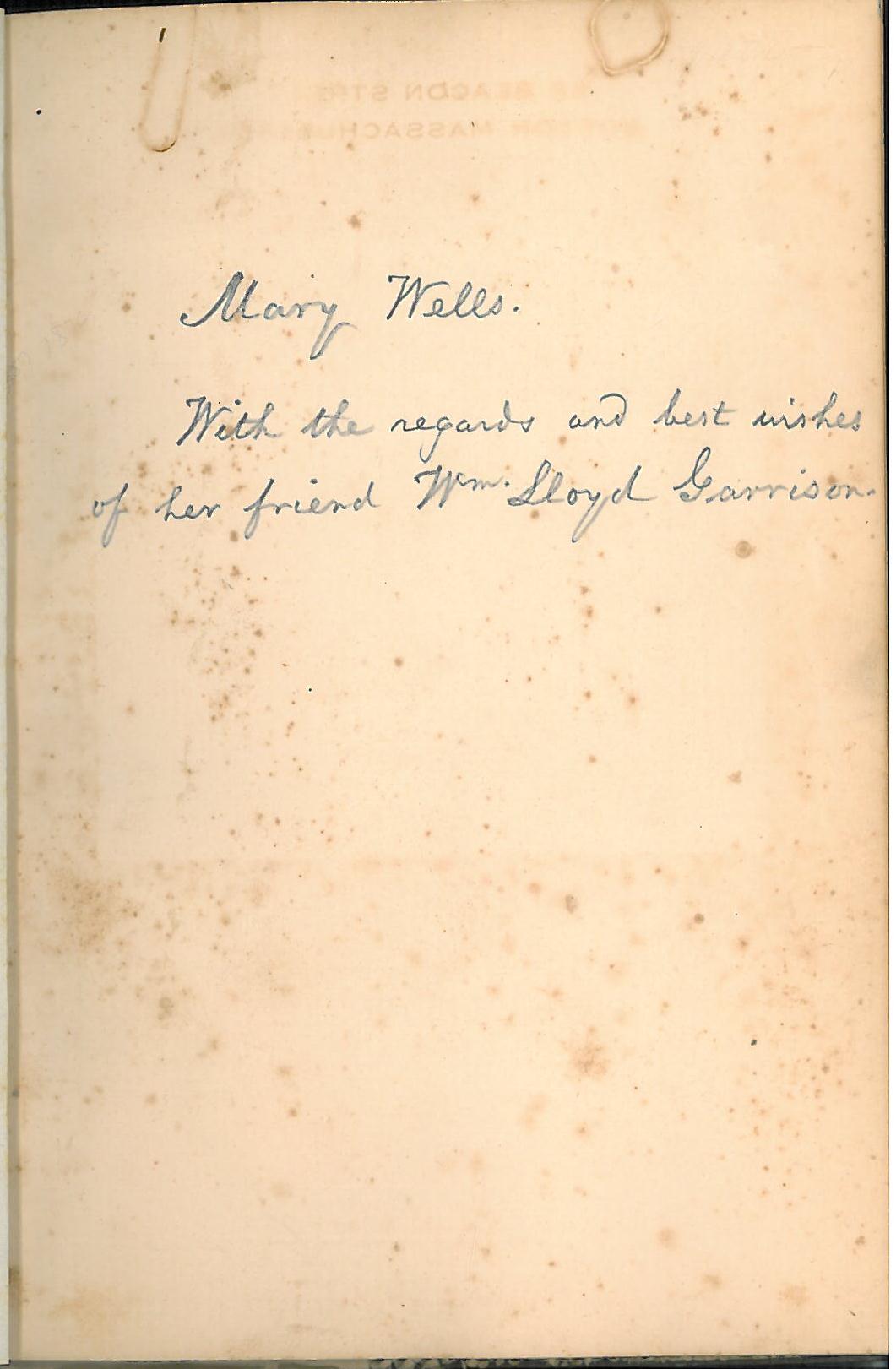

Garrison, William Lloyd. Helen Eliza Garrison: A Memorial. Cambridge: Printed at the Riverside Press, 1876.

8vo.; frontispiece portrait; faint foxing to preliminaries, front hinge tender; brown cloth, stamped in black and gilt.

First and only edition of a volume published by William Lloyd Garrison in honor of his wife Helen Eliza Benson Garrison (1811-1876), a major anti-slavery activist in her own right. Includes a photo of Mrs. Garrison; a 32-page memoir of Helen by Garrison; excerpts from press notices; and remarks delivered at Mrs. Garrison’s funeral by Lucy Stone, Samuel May, and others.

In 1830 Samuel May, his brother-in-law Bronson Alcott, and their cousin Samuel Sewell invited Garrison to lecture against slavery at a Connecticut church. In the audience was Helen Eliza Benson, the lovely 19-year-old daughter of a Rhode Island anti-slavery couple (her father, George, was president of the Windham County Peace Society, of which Samuel Sewell was secretary). Benson and Garrison, introduced by mutual friends, soon found they shared not only a profound belief in radical politics but also a deep mutual attraction: according to Garrison, “If it was not ‘love at first sight’ on my part, it was something very like it—a magnetic influence being exerted which became irresistible on further acquaintance,” (p. 18). The two married in 1834.

Helen’s marriage enabled her to become deeply involved in social reform activities. She and her husband read and discussed political tracts together, attended abolitionist meetings, and even ventured abroad on various human rights missions. The Garrison household became known as an open-door salon for leftist political figures; and just as Mr. Garrison was much more than a traditional host, Mrs. Garrison was more than an ordinary hostess: she planned and participated in contentious political debates; she invited emerging individuals and groups in whom she had an interest, especially those involved with suffrage work; and she would often be found with her shirtsleeves rolled up, stuffing envelopes, editing tracts, and engaging in other high- and low-level volunteer work.

While it might be argued that William Garrison was always, inherently, a feminist (he had early on insisted that sexual discrimination was as evil and pervasive as prejudice of the racial sort), it was through his wife that he became most exposed to the woman’s suffrage movement. Through Helen, female abolitionists like Lydia Maria Child and Abby Kelly Foster became allied with Garrison; and at her insistence Garrison submitted the famous statement in which he insisted that “universal emancipation” meant the redemption “of women as well as men from a servile to an equal condition.”

An uncommon volume which pays tribute to an uncommon partnership. The last notice printed in the book elegantly sums up the range of Mrs. Garrison’s interests and her role as a bridge between allied political movements:

At the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association held in Boston, January 25, 1876, the following resolution was adopted: ‘Resolved, that the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association deeply sympathize with their honored friend William Lloyd Garrison on the death of his wife, which occurred this morning, and that they extend to him their warmest sympathy in his great bereavement.’

(#4656)

Print Inquire